The 1927 release of the sound motion picture The Jazz Singer heralded the decline of silent films. The utilization of sound from then on made movies inaccessible to people who were deaf or hard of hearing (who had equally shared the film-viewing experience with the hearing audience during the silent film era). Simultaneously, however, it also made movies partially accessible to those who were blind or visually impaired (who never before had experienced movies with sound to guide them through the action).

Unfortunately, efforts to resolve this problem of inaccessibility in media as it related to the deaf did not begin for two decades. In 1947 the first true “captioning” occurred, as captions were placed between film frames, and while that helped alleviate some of the problem, it still wasn’t equal access.

Edmund Boatner

Edmund Boatner

Dr. Clarence O’Connor

Dr. Clarence O’Connor

As a response to this accessibility problem, Captioned Films for the Deaf, Inc. was established in 1949 in Hartford, Connecticut. Founders Edmund Boatner, superintendent of the American School for the Deaf, and Dr. Clarence O’Connor, superintendent of the Lexington School for the Deaf, organized the program as a private nonprofit corporation. Since captioning had quickly evolved to the superimposition of captions on film frames, both Boatner and O’Connor used said style of captioning for the films they obtained and loaned. In a few years, a library of thirty captioned theatrical films was acquired, and these films were free for use by deaf persons at residential schools, social clubs, and even in their home or apartment.

Although the program was initially a success, more financial support was needed than could be provided by private funds. The possibility of government support was explored at length. Organizations, including the National Association of the Deaf, the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf, the Conference of Executives of American Schools for the Deaf, and the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf, lobbied Congress on behalf of the program.

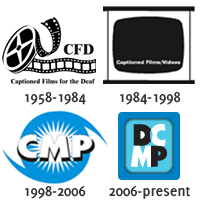

In 1958 the Captioned Films for the Deaf, Inc. became federal Public Law 85-905. The private corporation dissolved, and its entire collection of films was donated to the government. In July of 1959 the requisite funding was made available, and in October of that year the new federally run Captioned Films for the Deaf (CFD) program opened its doors to the public.

Malcolm J. Norwood

Malcolm J. Norwood

Although the initial purpose of the CFD was to provide subtitled Hollywood films to deaf people, teachers and other academic professionals were quick to recognize the potential of captioned films and other visual media as untapped educational resources. Consequently, the Congress amended the original law to authorize the acquisition, captioning, and distribution of educational films.

Malcolm J. Norwood [PDF], widely known as the “Father of Closed Captioning,” stated in his article titled “Captioned Films for the Deaf,” published in Exceptional Children in 1976:

The introduction of sound films in 1927 seemed to signal to deaf persons that they were to be completely isolated from the motion picture media. The threat was, of course, averted as the Captioned Films [for the Deaf] program made it possible once again for hearing impaired persons to share a common experience with the general public and to participate in the recreational and cultural aspects of motion pictures. Moreover, captioned films opened up avenues not only to recreation but also to important learning experiences.

The various incarnations of what is today the Described and Captioned Media Program

The various incarnations of what is today the Described and Captioned Media Program

In 1984 CFD introduced videocassettes and subsequently became Captioned Films/Videos (CFV). Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, 16mm films were withdrawn from the collection in favor of the more widely used VHS format. Likewise, in the mid-to-late 1990s, DVD, interactive CD-ROM, and streaming media gradually took over as the formats of choice in many schools and homes across the country. To reflect this evolution, CFV was again rebranded as the Captioned Media Program (CMP). This change occurred simultaneously with an increased focus on accessible media for K-12 students and their teachers and parents. In 2006 the CMP began serving students with vision loss, and once again changed its name, this time to the Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP).

Along the way, the program has been a pioneer in establishing quality standards for captioned media, particularly that which is used in educational settings. The Captioning Key: Guidelines and Preferred Techniques, a manual designed to encourage high-quality standards and serve as a teaching tool for beginning agencies, was released in 1994 as a one-stop guide for captionists seeking to hone their craft. Given its wide circulation and constant evolution, the Captioning Key remains an important component of the DCMP’s services today.

DCMP service to students who are blind or visually impaired involves another essential accessibility tool: description. Description (also called “audio description” or “video description”) is the verbal depiction of key visual elements in media and live productions. The concept of description has been around since the mid-1960s when Chet Avery, a U.S. Department of Education administrator who was blind, suggested to several consumer groups affiliated with the blind and visually impaired that they apply for funding to describe educational media, much in the same way that organizations affiliated with the deaf were applying for funding to caption films. However, description as a viable accessibility option in educational media and for broadcast television really began to take shape and form back in the 1980s when Dr. Margaret Pfanstiehl, founder and president of The Metropolitan Washington Ear, and her husband, Cody, trained volunteers to describe episodes of the PBS series American Playhouse.

Today approximately 4,000 captioned and described media items are available for free-loan to qualified DCMP members; students who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, visually impaired, or deaf-blind, and teachers, parents, and others who work with them, are eligible to borrow these materials.

The DCMP’s commitment to equal access for students with vision loss doesn’t stop with the distribution of described educational media. In October 2008 the DCMP released its Description Key. Developed in partnership with the American Foundation for the Blind, the Description Key is a first-of-its-kind reference for burgeoning describers seeking to improve access to educational media.

Read Captions Across America™ festivities are held in hundreds of schools across the country.

Read Captions Across America™ festivities are held in hundreds of schools across the country.

Finally, the DCMP has historically served a larger role than that of library service: advocacy. For example, in the last five years alone, the following initiatives have been established: Read Captions Across America™, which is in conjunction with NEA’s Read Across America; Caption it Yourself, a step-by-step tutorial to show individuals who shoot and upload their own media to the Internet how to caption; Equal Access in the Classroom, which is a production detailing description and captioning, providing teacher testimony supporting the need for these accessibility options in educational media, and overviewing the services provided by the DCMP; the completion of the first-ever educational media Description Key; and the DCMP Captioning Key, which is constantly evolving alongside technology and education.

This is why the DCMP is celebrating its 50th anniversary from September 2008 to September 2009: It was 50 years ago during that time frame that the law was enacted, the funding was provided, and the CFD officially began its long journey into history.

Because of the people who saw a need for equal access and acted upon it, and because of the time and effort of many who came after these initial few, captioning is practically ubiquitous now, and description is gaining momentum. Accessibility is more valuable than gold—it is a necessity—and captioning and description provide equal access to sources of information that would otherwise be inaccessible to millions of people in America. And that is why captioning, description, and the DCMP’s 50th anniversary are all particularly golden.